LGBTQ workers face extreme hurdles as the pandemic goes on

Thirty percent of LGBTQ people have had their hours reduced as a result of the crisis, compared to 22% of the general population.

Carl, a cisgender gay man working for a mattress company in Texas, was furloughed for eight weeks back in March when the pandemic hit. He said he felt relatively safe from the virus at that time.

Then, in May, when Texas reopened, Carl was told he would have to come back to work or it would be considered separation from the company.

Carl, who asked to be referred to by a pseudonym to protect his job security, said that even though Texas had made face masks optional, he was forced to assist customers without face coverings even as his employer says those safety precautions are mandatory for workers.

“I feel less valued than a profit margin,” he said.

Carl has depression and anxiety. He used the Family and Medical Leave Act at the end of June to take unpaid, job-protected leave while he faced a mental health crisis caused by working during a pandemic. His boyfriend has helped him stay afloat financially.

“I was feeling so low I wanted to hurt myself to get out of the job,” he said.

He said that if he ultimately decides to leave this job, he would probably have to work somewhere that doesn’t pay as well, such as a grocery store, since it is one of the few places where he has seen openings.

As states continue the reopening process, workers at restaurants, stores, and salons are given a difficult choice: They can go back to work and risk their lives or stay at home and hope they will find another job soon to support themselves and their families.

LGBTQ people, millions of whom work in these industries, are facing heightened economic vulnerability as well as greater risk of serious illness from COVID-19. And they say that many of their supervisors are ignoring safety precautions.

Last week, a Burger King employee in Santa Monica, California filed a complaint with state and county health authorities after a transgender coworker died. Angela Martinez Gómez’s managers had allegedly allowed her to come in for a week after showing symptoms associated with COVID-19.

At least one manager is alleged to have blamed her death on hormone injections.

Five million LGBTQ people in the United States work in jobs where they are regularly interacting with larger groups of people, putting them at greater risk of illness, as well as industries that have been particularly hard hit by the pandemic, according to a 2018 Human Rights Campaign analysis.

The analysis found that the top five industries in which LGBTQ people were most likely to work included food services, hospitals, K-12 education, colleges and universities, and retail.

Several workers who spoke with the American Independent Foundation work in restaurants and retail, which employs approximately 2.5 million LGBTQ people.

The pandemic has had a devastating effect on those workers.

Thirty percent of LGBTQ people have said their work hours have been reduced as a result of the crisis, compared to 22% of the general population. At least 42% have adjusted their household budgets compared to 30% of the general population, according to a PSB Research and Human Rights Campaign poll of 1,000 adults in the United States, conducted in April.

LGBTQ people already face tougher economic odds than the broader population: According to a 2019 report from the Williams Institute, a public policy and research group at UCLA that focuses on LGBTQ people, queer and trans individuals have a poverty rate of 21.6% compared to 15.7% for cisgender straight people. Transgender people and bisexual cisgender women had a higher rate of poverty, which were both at 29.4%.

Thousands of transgender people are also at risk of severe illness from COVID-19. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said that people who are immunocompromised, including those who have poorly controlled HIV or AIDS, and those with underlying medical conditions, such as lung disease, serious heart conditions, diabetes, and asthma, are at higher risk for severe illness.

According to a study from the Williams Institute, which uses data from the U.S. Transgender Population Health Survey, 208,500 transgender adults have asthma, 81,100 have diabetes, 74,800 are living with HIV, and 72,700 have heart disease, which put them at higher risk of serious illness from COVID-19 than people without these conditions.

Sixty-five percent of LGBTQ adults have pre-existing conditions, including HIV, diabetes, asthma, and heart disease compared to 51% of the U.S. population.

Some of the LGBTQ people working in restaurants and retail who spoke to the American Independent Foundation said they themselves were immunocompromised.

Cases of COVID-19 have reached at least 3.5 million in the United States. At least 137,319 have died.

On whether or not to return

Although Donald Trump has claimed that the economy is “roaring back,“ the unemployment rate still sits at 11.1%.

Kerith Conron, research director and Blachford-Cooper distinguished scholar at the Williams Institute, said that before the pandemic hit the United States, experts already knew that LGBTQ people, who had been struggling economically before, would be made even more vulnerable as a result of COVID-19.

“Poverty rates were higher for transgender people, bisexual adults, and LGBTQ people of color, so that means that people are going to feel they have to make certain choices about going back to work even if they don’t feel safe,” Conron said.

As states reopen, many LGBTQ workers are echoing those statements, saying they feel unsafe returning to work, have not returned at all, or quit after they realized they would not be safe. Some workers went back to their jobs but are once again on unemployment because their businesses shut down or reduced some services after states recommitted to safety measures.

Lee, a bisexual transgender nonbinary person with Type 1 diabetes who works as a host at chain restaurant in California — who asked that his name be changed to protect his current and future employment — said he didn’t have any financial choice but to return to work when the restaurant reopened and would still be at work if not for requirements that part of the the business be closed down during the pandemic.

Lee said the hiring manager at this job had been supportive of him as a transgender person, which made him particularly focused on keeping this job. However, after the restaurant stopped offering dine-in service more than a month ago, due to state and county safety requirements, he was forced to go back on unemployment.

“I’m not sure if it will be enough to pay rent and I’m not sure if I have to find another job and one that will put me more at risk, so it’s a stressful time,” Lee said.

Lee has looked at the possibility of working at local stores if he can’t go back to hosting.

Adele, a nonbinary lesbian who works as a server in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, who uses ve, ver, and vis pronouns, said that ve felt compelled to stay at ver workplace even though several employees tested positive for COVID-19 and ver managers didn’t inform any of the staff, which included a pregnant worker.

Adele said ve didn’t want to retrain at another restaurant or lose income by staying at home. Although the workplace isn’t as affirming for LGBTQ people as Adele would like, ve doesn’t think the environment would be much better elsewhere.

Jean, a lesbian restaurant worker who works at a chain restaurant in a small town in Texas, faces a similar struggle.

Jean, who uses they/them pronouns, has asthma and a nephew who is immunocompromised, leaving them particularly worried about getting sick.They have asked to work on to-go orders instead of serving food like they used to to stay safer. But that has meant that their hours have been reduced.

Jean doesn’t see many alternatives for employment in their rural community. They once worked at a psychiatric hospital but left due to several problems with the working conditions, including misogyny in management.

LGBTQ people who work in other businesses that are highly impacted by COVID-19, such as storage facilities and salons, have said they have either gone back to work and quit or never returned in the first place.

Matt, a bisexual man who lives in Colorado, worked in middle management for a storage facility and quit when his bosses refused to enforce mask policies, because they believed they would lose customers. Now he said he’s frustrated that he doesn’t have any income or health insurance. He said he plans to deliver food to make ends meet, like his girlfriend, until he can find a safer place to work.

April, a lesbian hairdresser who lives in a small town in Georgia with her wife and three children, said she decided not to return to work even though her salon reopened in May and has since been terminated. April and her wife Beth are both receiving unemployment.

After Beth lost her job from her university in 2018, she struggled to find work in the physical education field and took a job as a cashier at a gas station. But April convinced Beth not to stay at that job out of concern for exposure to COVID-19.

For years, the couple struggled to get health insurance because Beth’s previous employer wouldn’t recognize their marriage and fought the decision. After the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling on marriage equality in 2015, Beth finally won health insurance coverage for her wife. But like many LGBTQ people, they lost it again once they left their jobs to stay safe.

“I felt we were back on the path to financial security,” she said. “I was able to secure health insurance, as was she, and we were doing well. In March 2020, all of that ended.”

She added, “I don’t know when I’ll be able to safely return to work … We are basically hiding out at home with our three teenagers trying to stay safe and hoping there is a vaccine or some kind of solution soon.”

The salon was eventually forced to close once after a stylist tested positive for COVID-19.

“It only solidifies my choice to not return to work in such a busy salon. I’m not trying to die,” she said.

Fear of discrimination

On top of the safety concerns LGBTQ people have, the discrimination LGBTQ people face could make them more vulnerable to blowback if they raise concerns about virus safety measures or hamper their ability to get a new job.

“It makes sense that there would be heightened vulnerability to mistreatment on the job,” Conron said.

Despite the Supreme Court’s ruling that the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s Title VII’s workplace nondiscrimination protections apply to LGBTQ people and give LGBTQ people recourse against discrimination, it doesn’t serve as a form of prevention, Conron said.

“We know that LGBTQ people are more likely to experience discrimination at work,” she said.

LGBTQ people also suffer higher unemployment rates than the general population.

Even during the economic recovery, same-sex couples had higher rates of unemployment than different-sex couples, said Sharita Gruberg, senior director for the LGBTQ research and communications project at the Center for American Progress.

“Based on the information we have about how widespread experiences of discrimination are, the representation of LGBTQ people in low-wage jobs and issues like that, lead us to believe that the discrimination LGBTQ people folks face throughout their lives definitely has an impact on the higher unemployment rates for same-sex couples,” she said.

All but one worker said they were concerned about anti-LGBTQ discrimination in interviews for other jobs that may provide greater safety or were concerned about vulnerability to discrimination at their current job. Matt said he planned to hide his bisexuality from future employers. He said that coworkers allegedly used homophobic slurs when referring to his gay coworker and that he felt he was treated differently after he came out to coworkers.

Lee said he feared he wouldn’t get his current job but took the risk of coming out to the employer. Now Lee says he’s not sure how he feels trying to find another less risky job.

“I didn’t even tell [the employer] until I was walking out the door … I have had other trans friends who have been straight up denied jobs because they’re trans and I’m pretty sure I have [been denied jobs because of that as well],” Lee said.

“I don’t think I have evidence, but I’m pretty sure I’ve had interviews and applications thrown out because they could see that I was trans based off of name changes and stuff, so it can definitely be harder to get a job because of that discrimination.”

Adele, whose coworkers know that ve is a lesbian but not nonbinary, said that ve doesn’t think ve can speak up about safety issues at work because ve will be automatically dismissed by coworkers. Adele isn’t sure if that’s because ve is gay or because of ve is seen as “far left.”

“I don’t want to speak about it because I don’t want to ruffle any feathers. I need money,” Adele said.

Adele said ve is staying at this job because ve isn’t sure whether ve wants to stay in school full-time and isn’t sure whether ve would find a more LGBTQ-affirming workplace in their area.

Ve said coworkers haven’t “been rude” since ve came out at work, but one coworker has repeatedly hit on ver even after ve came out and ve is sometimes concerned that customers might notice something, like a rainbow bracelet ve wears, and not tip as well.

“It’s not like people leave a note like ‘Repent. Pray,’ but I have been worried about it, especially because I live in Alabama and we have a lot of older customers come in,” Adele said.

Carl said that considerations about which employers will treat him with respect can narrow his employment options.

“I do feel the burden of staying on guard for my own personal safety instead of feeling comfortable to speak freely,” Carl said.

“I don’t have that burden anymore at my current job, which may be what has kept me so long — what if it gets worse somewhere else?”

Published with permission of The American Independent Foundation.

Recommended

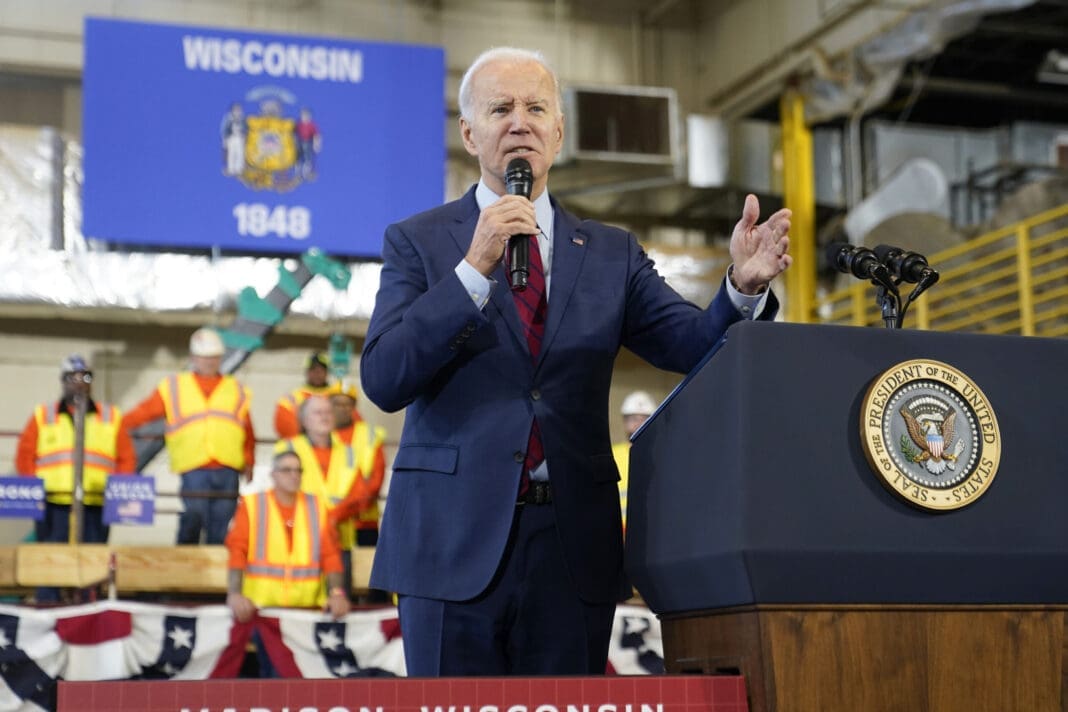

Biden calls for expanded child tax credit, taxes on wealthy in $7.2 trillion budget plan

President Joe Biden released his budget request for the upcoming fiscal year Monday, calling on Congress to stick to the spending agreement brokered last year and to revamp tax laws so that the “wealthy pay their fair share.”

By Jennifer Shutt, States Newsroom - March 11, 2024

December jobs report: Wages up, hiring steady as job market ends year strong

Friday’s jobs data showed a strong, resilient U.S. labor market with wages outpacing inflation — welcome news for Americans hoping to have more purchasing power in 2024.

By Casey Quinlan - January 05, 2024

Biden’s infrastructure law is boosting Nevada’s economy. Sam Brown opposed it.

The Nevada Republican U.S. Senate hopeful also spoke out against a rail project projected to create thousands of union jobs

By Jesse Valentine - November 15, 2023