'Build Back Better' could help the doctor shortage crisis in the US

The Democrats’ social spending package would invest $1 billion in medical and nursing school programs and would support medical students from underrepresented communities.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic set in, the United States faced a growing shortage of doctors and other medical care providers.

It’s a straightforward issue: The number of American doctors is shrinking despite the increased demand for medical care. By 2034, the United States may see a shortage of between 37,800 and 124,000 physicians, according to one recent study from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The pandemic has only exacerbated these trends. Facing near-constant virus surges, shortages of protective supplies, and the politicization of their lives and livelihoods, the burnout epidemic has pushed even more physicians out of the workforce. Indeed, roughly three in 10 health care workers have considered leaving the profession as a result of the pandemic, according to an April Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation poll.

But several provisions in the Build Back Better Act, Democrats’ wide-ranging social spending package, would work to combat this issue by investing billions of federal dollars in programs to increase the size and makeup of the health care workforce.

The package as passed by the House includes a patchwork of provisions intended to bolster the size and diversity of the health care workforce. It would invest $150 billion over the next 10 years in at-home and community-based health care — something advocates have long been calling for — and would earmark $1 billion for direct patient care.

The Association of American Medical Colleges is a vocal supporter of the Biden administration’s ambitious spending package, in part because of its investment in the next generation of health care workers.

Build Back Better would “help diversify the physician workforce, increase access to care for people in under-served urban and rural communities, take steps to prepare the nation to respond to public health emergencies, and address long-standing health inequities,” the group said in a statement.

One issue is that the American population is getting older as a whole. The U.S. Census Bureau projects that by 2034, Americans age 65 and older will outnumber children for the first time in the nation’s history. An aging population means increased demand for medical care in the long term, which puts even more stress on health care providers dealing with heavy workloads.

“What we’ve seen year after year is that those shortages, the demand for physicians is increasing,” Matthew Shick, a senior director of government relations and regulatory affairs at the Association of American Medical Colleges, told the American Independent Foundation.

American physicians — many of whom are baby boomers — are also retiring faster than new generations of doctors are coming into the field. But experts say the physician shortage isn’t solely a result of too few students are attending medical school.

One largely overlooked issue is the fact that U.S. hospitals don’t have enough room in their residency programs to train new doctors. In 1997, Congress capped the number and geographic distribution of Medicare-supported residency programs, creating a bottleneck that prevents many medical school graduates from entering the workforce in the first place.

Over the past 25 years, the U.S. population has grown by more than 67.2 million people, yet the number of U.S. hospital residency programs has remained virtually the same.

“However many residents a teaching hospital was training at the end of 1996, that’s essentially their cap,” Leonard Marquez, a senior director at the Association of American Medical Colleges, told the American Independent Foundation.

The Build Back Better plan would help to alleviate this bottleneck by establishing 4,000 new graduate medical education positions supported by Medicare. The federal spending package would also give $500 million to medical schools and $500 million to nursing schools, with priority given to schools that are designated as minority-serving institutions.

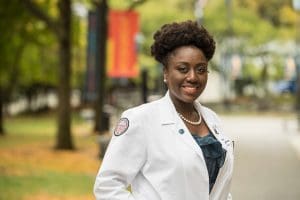

While the consequences of the residency program shortage may be hard to imagine, they are very real for medical students like Chantel Thompson.

Thompson, a fourth-year medical student at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine and national president of the Student National Medical Association, is currently applying to residency programs and hopes to one day work as an OB/GYN. Her dream is to help address existing racial disparities in American health care, especially the maternal mortality crisis that many Black mothers face.

“There are thousands of students who have put in the work, studied, paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for their education, and now have a medical degree that they can’t fully use,” Thompson told the American Independent Foundation.

Thompson, who was born in Philadelphia, highlighted Democrats’ efforts to support students from underrepresented communities who want to pursue careers in medicine. She cited the Build Back Better Act’s proposed Pathway to Practice Training Program, which would provide scholarships to minority students, first-generation college attendees, or those from rural communities pursuing medical studies.

The pandemic has disproportionately affected racial and ethnic minorities, yet a 2018 AAMC survey found that 56% of U.S. physicians are white, compared to just 5.8% who are Hispanic and 5% who are Black. Research has shown that patients are more likely to report high satisfaction with the care they receive if their race matches that of their health care provider.

If passed into law, Build Back Better wouldn’t solve the health workforce shortage entirely, nor would it automatically improve physician diversity. But it would make significant strides in the right direction, experts and advocates say.

“We need to invest not only in increasing the size of the workforce through residency training, but also shaping the workforce by improving the pathway into medicine, by improving how we provide care, and by improving access to care,” Shick said.

Those investments are desperately needed, he added, “to ensure the health of the nation.”

Published with permission of The American Independent Foundation.

Recommended

Biden calls for expanded child tax credit, taxes on wealthy in $7.2 trillion budget plan

President Joe Biden released his budget request for the upcoming fiscal year Monday, calling on Congress to stick to the spending agreement brokered last year and to revamp tax laws so that the “wealthy pay their fair share.”

By Jennifer Shutt, States Newsroom - March 11, 2024

December jobs report: Wages up, hiring steady as job market ends year strong

Friday’s jobs data showed a strong, resilient U.S. labor market with wages outpacing inflation — welcome news for Americans hoping to have more purchasing power in 2024.

By Casey Quinlan - January 05, 2024

Biden’s infrastructure law is boosting Nevada’s economy. Sam Brown opposed it.

The Nevada Republican U.S. Senate hopeful also spoke out against a rail project projected to create thousands of union jobs

By Jesse Valentine - November 15, 2023