The last place immigrants feel safe getting COVID vaccine is from ICE

Vaccines are slowly becoming available to immigrants in US custody. Whether they trust authorities enough to take them is another question.

Experts say the fraught history between U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the people it detains has created mistrust and hesitancy to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, even as prisons and detention facilities suffer constant outbreaks of coronavirus.

California public health officials announced earlier in March that those held in ICE-run facilities in the states were now eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine. In places like New York, officials are pushing prisons hard to administer doses as soon as possible, and present adequate plans detailing how they intend to do it.

That hasn’t done much to quell experts’ fears, however, that detainees will get their shots, even with availability.

Across the nation, over 9,500 detained immigrants have tested positive for COVID-19, and nine have died since the onset of the health crisis, according to the Los Angeles Times. According to a study published on Jan. 14, just one state — Louisiana — specifically noted immigration detention centers in its vaccination priority plan.

For the nearly 13,500 immigrants in ICE custody nationwide, things are slow going. Most states told Insider in February that they had not begun vaccinations for detained immigrants. Dozens of state health departments also told the outlet in the first two months of the year that ICE had not coordinated with them on a COVID-19 vaccination plan for detained immigrants.

But not all detainees may be willing to receive their vaccine doses — and given their past interactions with immigration law enforcement, it’s understandable.

Kiran Savage-Sangwan leads the California Pan-Ethnic Health Network and sits on the California Department of Public Health’s Community Vaccine Advisory Committee, which helps the state distribute vaccines equitably. In an interview on Monday, she told San Francisco-based radio outlet KQED, “We can’t expect folks that are detained to be receptive to getting the vaccine from the detention facility staff or from people associated with ICE. And that’s because of the really poor track record of medical care in these facilities.”

For years, immigration advocates and lawyers have worked to address allegations of medical abuse and neglect in ICE facilities.

Just this past year, at least 19 women held in an ICE facility in Georgia were subjected to unnecessarily aggressive gynecological treatments, at times without their consent, and were “coerced” into having hysterectomies, according to multiple media outlets and a panel of outside experts that investigated whistleblower claims.

Since 2017, there had been at least 39 deaths in ICE custody, according to an April 2020 report by the ACLU, Human Rights Watch, and National Immigrant Justice Center.

“Independent medical expert analyses … have found subpar care contributed to these deaths,” the groups said in a press release at the time. “Twelve of these deaths were by suicide while in detention. Two of the five detention centers our researchers visited had no mental health professional on staff. Detained immigrants told researchers about facilities taking a week to set a broken bone and that necessary medication, such as inhalers for asthma, were often not available.”

Eunice Cho, ACLU senior staff attorney, added, “In a global pandemic, these conditions — overcrowding, lack of access to medical care, staff who don’t speak Spanish, etc. — become even more deadly.”

As Dr. Sherita Golden, vice president and chief diversity officer for Johns Hopkins Medicine, noted earlier in March, “People of color, along with immigrants and differently-abled men and women have endured centuries of having their trust violated. We need to give people the facts about the vaccine’s safety and efficacy, and renew their trust toward health care in general.”

“It’s incumbent on health care organizations and leaders to help repair and restore that relationship,” she added.

Yvette Borja, staff attorney at ACLU of Arizona, said in a press call on Thursday that one solution to the trust issues in immigration facilities could be excluding authorities and detention center staff from the equation altogether.

“If there were to be some kind of initiative that was to be government-led and that wouldn’t involve ICE, then I think that’s something that could be potentially be productive,” Borja said. “ICE thinks about their role as a punitive way, and I think it would be refreshing to have a government entity that saw itself as prioritizing the health of people who are detained.”

Immigration advocate Michael Saavedra, legal coordinator of Youth Justice Coalition, added, “It would definitely be better for medical people, especially doctors, to talk to the prisoners and explain the side effects and explain everything to them.”

“Because of the disinformation coming from guards, especially if there’s rumors or there are side effects and people are going to die, etcetera, that fear-mongering needs to stop,” he said. “And they need to hear directly from medical staff.”

Corene Kendrick is deputy director of the ACLU National Prison Project, which advocates for the health, safety, and dignity of vulnerable populations in jails, prisons, and other places of detention. She said in the press call that even some prison staff were not taking the vaccine, undermining efforts to control the pandemic inside detention centers or the communities that surround them and adding to detainees’ hesitancy to take the shot.

The overall lack of education on the subject has complicated already existing issues.

Kendrick said incarcerated people who called into the ACLU National Prison Project’s hotlines have told them that no information is being given about the vaccine or how to get their second shot.

Even if there is information, she said, in at least one instance, “It’s literally a Xeroxed copy of the FDA insert that goes in the box of the vaccine that goes on for pages. It was written by an attorney and lists every side effect that might possibly occur and doesn’t really answer the questions.”

“Education is the key in order to get incarcerated people to accept [the vaccine],” Kendrick said.

“With more and more people accepting the vaccines, and then people who initially refused seeing that their friends didn’t have any bad side effects, they’re coming back and saying to the jail or prison staff, ‘you know what, I do want that vaccine,” she added.

Kendrick cited success stories in Oregon, California, and Massachusetts that proved education campaigns work.

California’s prison system, for instance, distributed handouts with useful information from Amend at the University of San Francisco, a program dedicated to reducing debilitating health effects in prisons and jails — an effort that led to upwards of 90% vaccine rates, she said.

Videos and in-language materials that explain how the vaccine works and why it’s important both for themselves and their community have also made a difference in increasing inoculations.

Published with permission of The American Independent Foundation.

Recommended

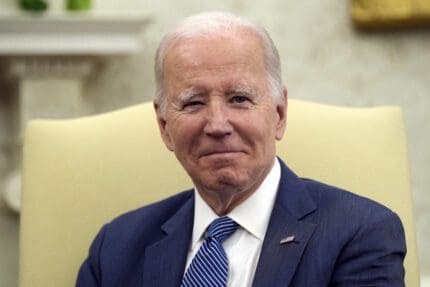

Biden campaign launches new ad focused on Affordable Care Act

Former President Trump has said he wants to do away with the popular health care law.

By Kim Lyons, Pennsylvania Capital-Star - May 08, 2024

Ohio doctors fear effects of emergency abortion care case set to go before U.S. Supreme Court

A federal law that allows emergency departments to treat patients without regard to their ability to pay will be under U.S. Supreme Court scrutiny this week, and Ohio doctors are concerned about the case’s local impact on emergency abortion care.

By Susan Tebben, Ohio Capital Journal - April 23, 2024

House GOP votes to end flu, whooping cough vaccine rules for foster and adoptive families

A bill to eliminate flu and whooping cough vaccine requirements for adoptive and foster families caring for babies and medically fragile kids is heading to the governor’s desk.

By Anita Wadhwani, Tennessee Lookout - March 26, 2024