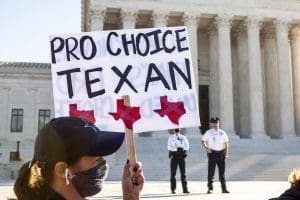

Hispanic and teen fertility rates increase after abortion restrictions

More than 16,000 babies were born in Texas in 2022 than in 2021, a new study from the University of Houston shows.

More Texas women had babies after the state banned nearly all abortions after six weeks of pregnancy, leading the state’s fertility rate to increase for the first time since 2014.

The 2022 fertility data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, analyzed by the University of Houston, offers the first concrete look at how many more women ended up carrying pregnancies to term as a result of the 2021 law.

More than 16,000 additional babies were born in Texas in 2022 compared to 2021, which comes to a 2% increase in the state’s fertility rate. Fertility rate is measured as births per 1,000 women between the ages of 15 and 44. The group that saw the largest increase was Hispanic women between the ages of 25 and 44, with an 8% increase over 2021.

“We knew that there would be an effect and, since we’ve seen initial data, we knew that it probably would be skewed in terms of greater Hispanic effect,” said lead author Elizabeth Gregory with University of Houston’s Institute for Research on Women, Gender and Sexuality. “But seeing the actual data, it makes it less of a theoretical discussion and more of a discussion the community has to have around what’s happening in people’s lives and how this affects individuals.”

Nationally, fertility rates declined slightly last year, in line with a yearslong trend. A big driver of that national decline is a 67% drop in teen birth rates over the last 15 years.

But now, Texas reversed that trend, documenting a 0.4% increase in its teen birth rates.

“We’ve seen big, ongoing declines, in which more and more teens presumably are accessing contraception or refraining from sex,” Gregory said. “So even though that looks like a small rise, it’s a big difference from the pattern of the years previously.”

In September 2021, Texas banned nearly all abortions after six weeks of pregnancy with a bill known as Senate Bill 8, and less than a year later, after the overturn of Roe v. Wade, expanded the prohibition to pregnancies from the moment of conception with a trigger law.

While the number of abortions plummeted — from 50,000 in 2021, to 17,000 in 2022 to just 40 in 2023 — it’s been hard to get a clear picture of what happened to the pregnant women who might otherwise have sought abortions. Some portion of them were still able to get abortions, either by traveling out of state or obtaining abortion-inducing medication online or from another source.

This fertility data offers the first accounting of how many of those pregnancies were actually carried to term and delivered in Texas. And it confirms advocates’ predictions that the impact of these abortion bans would not be felt evenly across all communities.

Hispanic women saw the greatest increases, while fertility rates among Asian women increased just slightly and Black and white women saw small declines. Gregory noted that the declines might have been larger for those groups if it wasn’t for the abortion bans.

“The results don’t signal that individuals of other groups are unaffected by the abortion ban, but they indicate that Hispanic women as a group are facing more challenges in accessing reproductive care, including both contraception and abortion,” Gregory said in a press release.

Women between the ages of 25 and 39 saw a steep increase in fertility rates, which the study links to child care issues and other barriers that prevent women who already have children from accessing out-of-state abortions.

“As we warned when SB 8 and [the trigger law] were passed over our objections, women of color — who are more likely to face challenges accessing reproductive care due to income, inability to take time off from work, lack of transportation or child care — have been the most affected,” the Texas Senate Democratic Caucus said in a statement.

Calculating post-Roe impact

A second study released this week on the impact of new abortion restrictions has caught widespread attention, including from Vice President Kamala Harris. The paper, published in the medical journal JAMA Internal Medicine, projects the potential number of rape-related pregnancies that have occurred in states that banned abortion after the overturn of Roe v. Wade.

Texas, which does not allow abortions in cases of rape or incest, had the largest estimate of rape-related pregnancies of the 14 states included in the analysis.

But measuring the number of sexual assaults, let alone how many resulted in pregnancies and how those pregnancies turned out, is a nearly impossible task. Sexual assault is a notoriously underreported crime and often occurs in the context of domestic violence, making people even less likely to speak out about their experiences.

To reach their estimates, the researchers analyzed several data sources, including the CDC’s National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey and data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, to estimate the number of sexual assaults against women of reproductive age. Neither of these data sets contain state-level numbers, so the researchers apportioned the estimate to each state based on FBI data of reported rapes by each state.

They then used historical data to estimate how many of those rapes were vaginal, meaning they could result in pregnancy, and how many of those vaginal rapes likely resulted in pregnancy.

Based on this analysis, researchers estimated 519,981 rapes resulted in 64,565 pregnancies in 14 states that have banned abortion. The estimate does not factor in how many of those people might have traveled out of state or found another way to end their pregnancy, or how many of them might have carried to term regardless of the abortion laws.

“Even in the context outside of an abortion ban, a lot of survivors of rape have endured intimate partner and family violence, and those circumstances make it even more difficult for them to get the reproductive health care that they need,” said Kari White, executive director of Resound Research for Reproductive Health, the collective that produced the JAMA-published research. “Abortion bans just put more obstacles in their way.”

White said the goal of the research was not to pin down exactly how many more babies were born as a result of sexual assault, but rather to give a sense of how many survivors of sexual assault might be dealing with an unexpected pregnancy in a state that has limited their reproductive health care options.

She said they were surprised by how high the estimates were, and that it reaffirmed for the researchers that this is a common experience.

“We hope it’s going to draw attention to the fact that people’s lives are being impacted by sexual violence,” she said. “Survivors need our support, regardless of the personal decision that they decide to make about their pregnancy. But for those folks who do make a decision to have an abortion, they need access to safe and legal abortion care.”

Dr. Samuel Dickman, the lead researcher on the study, is medical director of Planned Parenthood of Montana, but used to practice in Texas.

“Rape survivors who become pregnant deserve to make informed, personal decisions about their pregnancy, and state-level abortion bans – even those with exceptions – don’t allow them to do that,” Dickman said.

At the Houston Area Women’s Center, the domestic violence and sexual assault services center for Harris County and the region, they frequently see clients who got pregnant due to a sexual assault. That hasn’t changed since the abortion laws went into effect, said Letitica Manzano, senior manager of sexual assault survivor services.

“What’s changed is the clients have the added trauma of not being able to control decisions over their own bodies after they were sexually assaulted and experienced this sense of powerlessness over their body,” she said. “What’s changed is how we can talk to them about their options.”

Before the abortion laws went into effect, Manzano said they proactively offered clients the full range of options available to them. Now, they wait to see if a client brings up the idea of abortion, and then they explain the limitations of the law.

Through the support groups that Houston Area Women’s Center hosts, Manzano said she’s been able to see the wide range of experiences of women who were impregnated as a result of sexual assault. Some decide to terminate, but others carry to term and raise the child.

“Some of them are able to have a wonderful relationship with their child,” she said. “Others say they really struggle with connecting with this child … It’s a sense of sadness that they’re carrying into that relationship. And it’s a sadness for me, as a trauma counselor, of what life might be like for that child.”

When the ban on nearly all abortions after six weeks of pregnancy went into effect in 2021, Gov. Greg Abbott said there was no need for a rape exception, because Texas was going to focus on making sure “we eliminate all rapists from the streets of Texas.”

The estimates from the JAMA study, and Manzano’s experience working with survivors every day, indicate Texas still has a long way to go to achieve that goal.

“We’re doing the prevention work, and we’ve got good partners in that,” Manzano said. “Is it enough? No.”

Recommended

Biden campaign launches new ad focused on Affordable Care Act

Former President Trump has said he wants to do away with the popular health care law.

By Kim Lyons, Pennsylvania Capital-Star - May 08, 2024

Ohio doctors fear effects of emergency abortion care case set to go before U.S. Supreme Court

A federal law that allows emergency departments to treat patients without regard to their ability to pay will be under U.S. Supreme Court scrutiny this week, and Ohio doctors are concerned about the case’s local impact on emergency abortion care.

By Susan Tebben, Ohio Capital Journal - April 23, 2024

House GOP votes to end flu, whooping cough vaccine rules for foster and adoptive families

A bill to eliminate flu and whooping cough vaccine requirements for adoptive and foster families caring for babies and medically fragile kids is heading to the governor’s desk.

By Anita Wadhwani, Tennessee Lookout - March 26, 2024