Ilhan Omar wants Biden to assign a point person to address Islamophobia. Will it help?

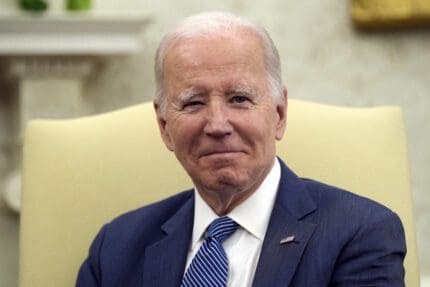

The request for a special envoy, a role President Joe Biden employed to address the political crisis in Haiti recently, presents major bureaucratic hurdles, diplomats say.

Minnesota Rep. Ilhan Omar and a group of two dozen Democratic lawmakers sent a letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken on July 20, urging him to designate a special envoy to address rising Islamophobia.

“As part of our commitment to international religious freedom and human rights, we must recognize Islamophobia as a pattern that is repeating in nearly every corner of the globe,” Omar wrote. “… For this reason, we are writing to strongly urge you to appoint a Special Envoy for Monitoring and Combatting Islamophobia.”

A special envoy may be appointed by the secretary or the president, without Senate approval, to manage an international crisis. But experts say the role isn’t always as useful in practice as it is in theory.

Just last month, a pickup driver in London, Ontario targeted Muslims in a mass shooting that killed four. And the Council on American Islamic Relations released a midyear report citing at least 500 documented complaints of anti-Muslim incidents in the United States in 2021 so far, including threats against mosques, vandalism, an attempted stabbing outside a mosque, and targeted attacks against women wearing hijab. Omar suggested in her letter that those incidents proved a need for a more concentrated effort to stop the problem.

The congresswoman’s plea for a special envoy isn’t the only recent instance of Democrats aiming to tackle a problem using the diplomatic tool. After Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated earlier this month, President Joe Biden appointed a special envoy to handle things in the Caribbean nation, with its spiraling geopolitical crisis.

But foreign service officers are critical of the ill-defined role, which was habitually used by President Barack Obama’s administration and has been known to cause headaches across the State Department. Omar’s proposal, while admirable, may simply not do enough.

“[Envoys] don’t actually have clear authorities or resources,” Brett Bruen, a career foreign service officer who served as Director of Global Engagement under the Obama administration, told The American Independent Foundation. “They walk around with fancy titles, and they’re trying, most of the time, to figure out where they can fit in or are able to make a contribution, but they in many cases just end up wasting a lot of time because you then have turf battles over who controls what.”

The role dates back to President George Washington’s tenure, when he sent Gouverneur Morris, a Founding Father who helped pen the preamble to the U.S. Constitution, to Great Britain in 1789 to hammer out a treaty and address several other outstanding problems between the two nations.

Today, envoys are often appointed by presidents to signal they’re taking an issue seriously and that the task requires some specialized manpower.

“The idea really is essentially — this is something important and in our current bureaucracy we do not elevate its importance enough in our hierarchy,” Elizabeth Shackelford, a career diplomat with the State Department, who stepped down in 2017 with a scathing resignation letter criticizing the Trump administration, said in a phone call.

Examples of the post under the Biden administration include a special envoy to advance the human rights of LGBTQI+ persons, one to manage the global COVID-19 response, and another to oversee nuclear nonproliferation, as well as special envoys to deal specifically with crises in Sudan, Syria, Yemen, and now Haiti.

The State Department also previously assigned a special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism, a role Omar proposed to mirror in her letter earlier in July.

Special envoys also typically have more leeway than most other government employees.

“They have a focused set of responsibilities,” Earl Anthony Wayne, a former career ambassador to Afghanistan, Argentina, and Mexico, told The American Independent Foundation. “They still have to coordinate with other people when it comes to making any changes to U.S. policy or mobilizing any additional U.S. resources. But they are free to travel and act diplomatically, free of a number of the bureaucratic constraints and the constraints of having other responsibilities.”

That freedom comes with criticisms. Envoys have been known to rankle foreign service officers, who claim the post has a tendency to be overused, and often becomes a way to score political points on a given issue.

“You got to be prudent here — there is a danger of having too many special envoys, because they all criss cross each other and they can make coordination harder,” Wayne said.

And consolidating positions with overlapping mandates is not so simple. Special envoys are much easier to create than they are to eliminate.

Rex Tillerson, former President Donald Trump’s secretary of state, moved to do away with several special envoy positions in 2017, but legislators and interest groups pushed back. According to the American Foreign Service Association, most of those positions still exist, though many remain unoccupied.

Having too many special envoys can frustrate allies as well.

Such was the case in Haiti, where Haitian Senator Patrice Dumont criticized Biden’s special envoy for meeting with Haitian officials earlier in July.

“(This is just) one more American official. But to do what?” Dumont told Voice Of America. “Haiti is an adult and should resolve its own problems.”

Critics argue that special envoys simply don’t fit well into the State Department’s bureaucracy. According to a 2015 report from the American Academy of Diplomacy, an independent association of former senior ambassadors and high-level government officials, envoys typically bring staff in from the outside, operate outside of normal procedures, and pursue their agenda without integrating larger national interests into their work.

“A number of times, special envoys go out and do things without coordinating with other parts of the state department or other agencies even though they’re crossing different policy lines, and thus they create more complications and sometimes do things that are interfering with other policy priorities,” Wayne said.

Diplomats chafe at the idea of political appointees coming in to do work that typically falls under the purview of career foreign service officers. They say special envoys are inherently political and create turnover issues between administrations.

Many are unsure, then, of whether or not Omar’s proposal is the right approach to tackling the global issue of anti-Muslim hate.

The request deserves careful attention, Wayne said, and might be better addressed through existing State Department channels, like the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

Others worry a new position could duplicate other posts or that the mandate would be too open-ended.

There are already positions slated for an ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, a special representative for Muslim communities, a special representative for religion and global affairs, and a special envoy representative to the Council of Islamic Cooperation. All are currently vacant.

On July 30, Biden announced several nominees to key religious affairs roles, including the antisemitism special envoy, an ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, and two commissioners to address international religious freedom.

“If you have three people who are the senior person in relation to the White House on this issue, it can really reduce the influence of any of those individual roles, because it makes it less clear who has leadership on it,” Shackelford said.

The same criticism is being lobbed against Biden for appointing Daniel Foote as special envoy for Haiti, as the nation already has an ambassador that coordinates diplomatic efforts there.

“I thought this was a crazy use of a special envoy,” Shackelford said.

If Biden does decide to appoint another envoy, he should hire a career official for the job, argued Bruen. Otherwise it’s easy to imagine the next Republican president leaving the post vacant, as Trump did with a number of special envoy positions.

“Just take Islamophobia as one example,” he said. “This is not something you’re going to be able to fix in two to three years. If we truly want to develop and execute a serious strategy then we need to have people that are able to provide leadership on the issue over the course of an extended period of time.”

He added, “If these are truly difficult, intractable problems, then you ought to be sending someone who can work on them over the long-term.”

Published with permission of The American Independent Foundation.

Recommended

Florida abortion ban puts GOP Rep. Anna Paulina Luna’s anti-choice views in spotlight

Luna supports abortions bans with no exceptions for rape

By Jesse Valentine - May 07, 2024

Republican Caroleene Dobson wants Alabama abortion ban to go nationwide

Dobson is the Republican candidate in what will be one of the most-watched House races of 2024.

By Jesse Valentine - April 30, 2024

Direct mailers distort California Democrat Will Rollins’ record

Rollins, a former federal prosecutor, is challenging incumbent GOP Rep. Ken Calvert.

By Jesse Valentine - April 25, 2024