My father is one of the vulnerable seniors most at risk from GOP's cruel Medicaid cuts

More than 1.4 million Americans are receiving nursing home or other long-term care paid for by Medicaid. One of them is my father. My father is now 77 years old and has a rare form of dementia. When he became unable to care for himself in his home, I took him into my home and […]

One of them is my father.

My father is now 77 years old and has a rare form of dementia. When he became unable to care for himself in his home, I took him into my home and cared for him there. But when I was no longer able financially, physically, and emotionally able to do so, my father moved to a Medicaid-funded facility.

To qualify for Medicaid funding for long-term care, you have to meet two types of criteria: financial and medical. To put it bluntly, you have to be both very poor and very infirm.

Under current Medicaid law, the financial criteria mandate that an individual have no more than $2000 in total assets (or $3000 for a couple) in order to qualify. Contrary to many people’s misunderstanding, Medicare — the federal universal health care program for everyone over 65 and for many people under 65 with disabilities — does not pay for long-term or “custodial” care.

Not everything a person owns counts toward the $2-3000 asset total. Your home does not count, if you are living in it and it has below a certain amount of equity. But once you are no longer living in your home on a permanent basis, the property becomes subject to the asset calculation.

In other words, when you require full-time care for the rest of your life, your home must be sold and the proceeds paid to Medicaid. Other assets that do not count toward financial eligibility determination include personal effects, such as “wedding and engagement rings,” and your “burial spaces.”

If your assets exceed $2-3000, you have to do what is commonly called a “spend down,” using all of your savings and selling everything defined by Medicaid as a “resource” to pay for your own care, until you only have that few thousand dollars left.

Spend-downs can happen very quickly; the average costs for nursing home care in the United States range from $5,000 per month to over $25,000 per month. In addition, once Medicaid begins paying for your care, any monthly income (pensions, Social Security, etc.) is paid directly to Medicaid.

Meaning: You must be poor — very poor — before Medicaid will pay.

In addition to being very poor, you must be very infirm to qualify for Medicaid funding for long-term care. There is no automatic eligibility based on diagnosis. Rather, a Medicaid worker comes out to do an in-person assessment of your ability to perform what are called “activities of daily living,” or ADLs. The definition of ADLs includes your ability to complete six, very primitive self-care tasks: bathing, dressing, toileting, incontinence care, transferring, and eating.

These tasks are indeed as straightforward as they sound. “Bathing” means can you remember to wash yourself and physically do so without falling or self-injury. “Dressing” means can you pick out appropriate clothing and physically put it on and take it off without help.

“Toileting” means can you get off and on the toilet, clean yourself, and/or change any catheters or ostomy bags. “Incontinence care” means, if you are unable to retain your urine or feces, can you change in and out of an adult undergarment, clean yourself, and/or change any catheters or ostomy bags.

“Transferring” means can you move your body from a bed or chair into standing position or into a wheelchair or walker without assistance. And “eating” means can you remember to eat without verbal prompts if food is placed before you, bring food from a plate or bowl into your mouth with a utensil, or manage your own feeding tube or veinous feeding system.

If you cannot do some or any of these activities to varying degrees, you might be medically eligible for Medicaid-funded long-term care.

Thus, you must be infirm — very infirm — before Medicaid will pay.

The lives of more than a million very poor, very infirm Americans are at stake if Medicaid is cut.

The most vulnerable among us — our fathers, our mothers, our grandparents, our spouses, our neighbors — are the people whose long-term care funding is at risk. And, by definition, they have no resources and nowhere else to go for care.

If you have a story like mine, you can choose to make your voice heard. Your elected lawmakers in the House and Senate need to hear from all of us facing harrowing situations like this, to help them understand that they cannot allow these Medicaid cuts to happen, and to inflict further harm and uncertainly on people who are already so vulnerable.

Tell your story and act on behalf of those you love who are unable to act for themselves.

Recommended

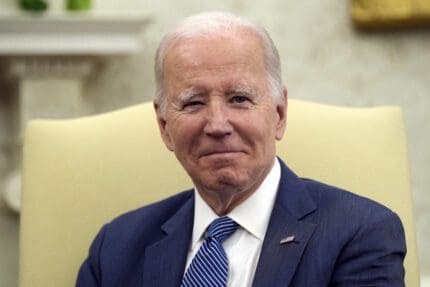

Biden campaign launches new ad focused on Affordable Care Act

Former President Trump has said he wants to do away with the popular health care law.

By Kim Lyons, Pennsylvania Capital-Star - May 08, 2024

Ohio doctors fear effects of emergency abortion care case set to go before U.S. Supreme Court

A federal law that allows emergency departments to treat patients without regard to their ability to pay will be under U.S. Supreme Court scrutiny this week, and Ohio doctors are concerned about the case’s local impact on emergency abortion care.

By Susan Tebben, Ohio Capital Journal - April 23, 2024

House GOP votes to end flu, whooping cough vaccine rules for foster and adoptive families

A bill to eliminate flu and whooping cough vaccine requirements for adoptive and foster families caring for babies and medically fragile kids is heading to the governor’s desk.

By Anita Wadhwani, Tennessee Lookout - March 26, 2024