Trump's failed response allowed COVID to surge in federal prisons

‘It was complete chaos and no one seemed to know the answers,’ one female inmate told the American Independent Foundation.

Andrea Circle Bear was five months pregnant when a judge sentenced her in January to 26 months in federal prison for “unlawfully and knowingly” allowing methamphetamine to be distributed on her property.

On March 20, the Federal Bureau of Prisons transferred Circle Bear from a local jail to FMC Carswell, a federal prison medical facility in Fort Worth, Texas — more than 1,000 miles away from her home on the Cheyenne River Sioux Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Within two weeks of Circle Bear’s arrival at the Fort Worth facility, she developed a fever, dry cough, and other symptoms of the coronavirus.

On March 31, she was taken to a local hospital and put on a ventilator.

On April 1, she gave birth to her baby by cesarean section.

And on April 28, Andrea Circle Bear died at the same hospital where she had just given birth.

She was 30 years old.

She was the first documented female federal prisoner to die from the coronavirus.

But she wouldn’t be the last.

In the final days of the 2020 presidential election, Donald Trump has claimed a moral victory over the coronavirus pandemic, even as the virus continues to rage across the country. An Oct. 27 White House press release listed “ending the COVID-19 pandemic” as one of Trump’s signature achievements while in office. That same day, the United States recorded more than 73,000 new cases of the virus, as well as 985 deaths.

White House spokesperson Alyssa Farah later admitted the press release was “poorly worded,” but added that “because of the president’s leadership, we are rounding the corner on the virus.”

Over the past eight months, America’s jails and prisons have become epicenters of the virus’s spread. This includes the federal prisons and other detention facilities that fall under the purview of the Bureau of Prisons, the Department of Justice, Attorney General William Barr, and ultimately, Trump himself.

The following is a story from one at-risk inmate inside Trump’s federal prison system — a 48-year-old woman who asked to be called “Janet” for the purposes of this story.

Janet is an inmate at FMC Carswell, the same federal prison medical facility where Andrea Circle Bear died in April. The minimum security prison detains women who are already ill or are otherwise vulnerable to COVID-19.

In July, the Bureau of Prisons reported that 509 women at FMC Carswell had tested positive for the virus.

Janet, who asked not to use her real name for fear of retaliation, told the American Independent Foundation that prison staff have failed to protect incarcerated women.

“We were not provided proper sanitation items,” she wrote. “We were not locked down as soon as the first inmate tested positive in the facility because we were still going to the dining hall to get our meals while still being in contact with ladies from other units.”

She continued: “It was complete chaos and no one seemed to know the answers.”

In August, Janet developed a cough and a runny nose. Then one of her lungs started to feel like it was burning. She tested positive for COVID-19 and was placed in quarantine.

Janet is a breast cancer survivor, making her even more vulnerable to the virus. But when she asked for a chest X-ray to see if the virus had affected her lungs, the prison doctor declined.

When she complained about her lung pain further, the doctor suggested it was acid reflux and prescribed her famotidine, also known as Pepcid.

This type of medical treatment isn’t the exception, but is the norm in federal prisons, according to Janet.

“Nothing at all was done with my complaint,” she wrote, adding, “BTW, they are using Pepcid for the treatment of COVID.”

Last week, the American Civil Liberties Union lodged a complaint against the Federal Bureau of Prisons demanding more transparency about the virus’ spread in federal correctional facilities.

America’s jails and prisons quickly became epicenters of the virus’ spread. Since the start of the pandemic, more than 252,000 people in U.S. jails and prisons have been infected, and at least 1,450 prisoners and prison employees have died, according to the New York Times.

U.S. correctional facilities are powder kegs for disease transmission. They have consistently led other high-risk institutions — such as meatpacking plants and nursing homes — in their rate of infection and death toll. The rampant overcrowding found in American jails and prisons makes social distancing virtually impossible.

In one recent study published in the journal Health Affairs, researchers found that 15.7% of all coronavirus infections in the state of Illinois between March and April could be linked back to one source: Cook Country Jail in Chicago.

“[We forget] these institutions are not simply contained spaces, but a part of our communities,” Eric Reinhart, one of the study’s researchers, said. “They’re very porous. People go in and they go out.”

In March, Attorney General William Barr directed the bureau to transfer federal prisoners to home confinement “where appropriate to decrease the risks to their health.” Between March and May, nearly 11,000 U.S. prisoners requested compassionate release due to the pandemic. The bureau approved just 11 of the requests, the Marshall Project reported.

Somil Trivedi, the ACLU’s lead attorney in its Bureau of Prisons lawsuit, said the agency’s “refusal to move people out of facilities” is its “biggest failure.”

“There are two issues going on in jails and prisons,” Trivedi told The American Independent Foundation. “First, the conditions inside the facility: the lack or shortages of hand sanitizer, laundry, masks, gloves — all of the hygiene protocols we take for granted.”

The second issue, Trivedi said, is “the inability to do social distancing.”

“It’s physically impossible unless you get people out,” he added.

Trivedi pointed out that while it’s easy for the general public to feel little compassion toward prisoners, they’re not the only people the virus will impact.

“If you want to be selfish about it, these things don’t stay confined to prison and jail settings,” he said. “I don’t expect a lot of the world to care about the lives of prisoners. That’s just where we are.”

Still, he added: “We deserve to know why this response has been this botched.”

Trivedi noted that the Trump administration’s lack of concern for civil rights is evident in the bureau’s pandemic response. “It’s what happens when you have people hellbent against recognizing people’s civil rights. People in jail and prison never stood a chance.”

In a statement to The American Independent Foundation, the Bureau of Prisons defended its record, arguing that the bureau has taken abundant precautions in the interest of inmates’ and employees’ health and safety.

“The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) has taken swift and effective action in response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), and has emerged as a correctional leader in the pandemic,” a spokesperson wrote. “As with any type of emergency situation, we carefully assess how to best ensure the safety of staff, inmates and the public. All of our facilities are implementing the BOP’s guidance on mitigating the spread of COVID-19. That guidance can be found on our website. We will continue to evaluate our mitigation strategies and make adjustments as needed.”

“We remain deeply concerned for the health and welfare of those inmates who are entrusted to our care, and for our staff, their families, and the communities we live and work in,” they concluded.

Still, federal inmates like Janet may have reason to reject the idea that prison staff are deeply concerned for their well-being.

“We were yelled at by two lieutenants not to ask any questions and to stay in our rooms. I was never even informed that I tested positive,” Janet wrote. “I was simply handed a box and told I had only a few minutes to pack limited items.”

“I was told by several other inmates that were being quarantined on the mental health floor that their food trays were being delivered by being kicked through the doorway,” she continued. “Their doors were locked 24/7 and they weren’t allowed out. I was told that they had to bang on the doors for a long time to get the guards’ attention to get any help for their deteriorating roommates.”

“I have seen officers tell inmates to just put in a sick call request when they clearly weren’t feeling well instead of calling the clinic and having them rapid-tested,” she added. “It was very heartbreaking for me to feel this completely insignificant.”

Published with permission of The American Independent Foundation.

Recommended

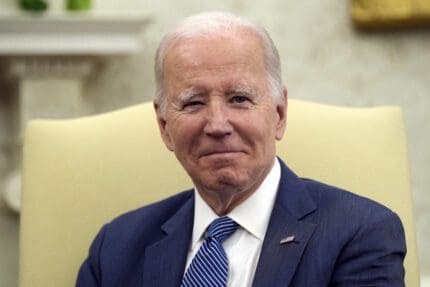

Biden campaign launches new ad focused on Affordable Care Act

Former President Trump has said he wants to do away with the popular health care law.

By Kim Lyons, Pennsylvania Capital-Star - May 08, 2024

Ohio doctors fear effects of emergency abortion care case set to go before U.S. Supreme Court

A federal law that allows emergency departments to treat patients without regard to their ability to pay will be under U.S. Supreme Court scrutiny this week, and Ohio doctors are concerned about the case’s local impact on emergency abortion care.

By Susan Tebben, Ohio Capital Journal - April 23, 2024

House GOP votes to end flu, whooping cough vaccine rules for foster and adoptive families

A bill to eliminate flu and whooping cough vaccine requirements for adoptive and foster families caring for babies and medically fragile kids is heading to the governor’s desk.

By Anita Wadhwani, Tennessee Lookout - March 26, 2024